俄罗斯有伏特加,韩国有烧酒,日本有清酒,而中国有白酒。像其他酒类一样,白酒是国家的象征、社会的润滑剂、商界的粘合剂、文化的洗礼,然而不仅于此,白酒还是身份的标志。

Russia has vodka, Korea soju, Japan sake, and China – baijiu (bye-joh). Like its cousins, baijiu serves as a national symbol, a social lubricant, a business sealant, a cultural baptism, and not the least of all, a mark of distinction. Rookies gag on its infernal flow, but a cultured person would never turn down a chance to clink glasses. As one Chinese friend puts it, “To the older generation, baijiu is a habit – there is no good or bad to it. It’s a part of the culture.”

因此,当去年我在中国做生意时,白酒给我带来了惊喜的发现,而且我意识到我的大部分同事都对白酒嗤之以鼻。我毫不掩饰地承认,我对白酒也没有兴趣,但是我很久以前就明白,白酒将是在中国展开销售的重要环节,不,可以说是关键的环节(除了啤酒销售外——那是我的老本行)。

It therefore came as a pleasant surprise to me when I started doing business in China last year and realized that most of my associates turned their noses up at it. I unabashedly admit that I have no taste for the stuff, but I accepted long ago that it would be an important – nay, critical – aspect to sales in China (let alone beer sales, which was my industry).

而我遇到的情况却显示,1980年前和1980年后出生的人对此存在明显的分歧。尽管老一代人显然喜欢在聚会上用传统的白酒助兴,可是年轻的客户却害怕提议喝点白酒。年轻人会很快拿出啤酒和香烟,如果我对这两样都拒绝的话,他们也不会坚持。然而,上年纪的人会大肆宣传白酒的好处,如果打断他们的表演,可能会搞砸这次商业交易。

What I instead encountered was a distinct split between people born before and after 1980. While the older generation clearly preferred to slicken meetings with the traditional liquor, the younger clients cringed at the suggestion of it. The latter group was quicker to offer a beer or cigarette, and did not press when I turned either down. The older group, however, had a song-and-dance centered on baijiu, and to interrupt this show would be to derail the business transaction.

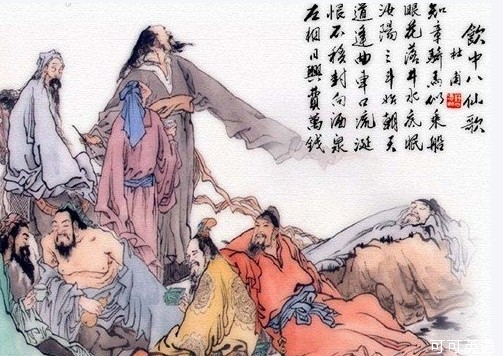

大多数在中国生活的人都参加过不止一次的“白酒秀”。你可以想象一下,一群中年人围坐在圆桌旁边,在沸腾火锅的助兴下寒暄致意,席间相互碰杯敬酒。如果有人向你敬酒的话,你要向后推开自己的椅子站起来,双手举起自己的瓷酒杯,表现出“热情”(热忱的友善)。要表现出热情,就要有文化,敬酒为热情洋溢的夜晚叩开了大门。席间也许会谈生意,也许没有,如果宴席一方把醉酒的另一方送上出租车,说明交易已经成功达成。

Most who have lived in China have participated in “the baijiu show” more than once. Picture a group of middle-aged people seated around a circular table, pleasantries underscored by a bubbling hot pot and punctuated by the clinking of cups. When someone offers to cheers you, you shove your chair back and jump to your feet, grasping your own porcelain teacup of baijiu with both hands to show “reqing” (passionate friendliness). To have reqing is to have culture, and the offering of baijiu opens the floodgate to a night of reqing. Business talk may or may not come up, and the deal is successfully closed only when one party carries the other out to a taxi.

我的年轻客户也一样——如果说不是比这更热情的话——对于友好接待他们的啤酒供应商很感兴趣,不过他们会找到其他的方式来表现热情。没有火锅和昂贵的白酒,取而代之的是便宜的青岛啤酒,我们在觥筹交错间寻找共同的兴趣。音乐、电影和新闻动态都是最常见的话题。智能手机在我们的谈话中经常出现,因为我们会提到新闻报道、博客或微信。对于中国来说,互联网使年轻一代了解社会弊端,认清假大空。由于这种同属一代人,我们心照不宣地拉近了关系,知道我们必须尽快为这个荒谬的世界承担责任,通常像喝下的白酒那样辛辣而灼热。

My younger clients are just as – if not more – interested in befriending their beer supplier, but they find other ways to exhibit reqing. Instead of hot pot and expensive liquor, we clink bottles of cheap Tsingtao and search for common interests. Music, movies, and current events are the most common topics. Smartphones footnote our conversations as we reference news articles, blogs, or WeChat. For China, the internet has contributed to a generation of young adults that, informed of their society’s follies, are disillusioned from its greatness. We tacitly bond over this generational oneness, knowing that we must soon shoulder responsibility for a ridiculous world that is often as stinging and fiery as a gulp of baijiu itself.

当这些二十几岁的年轻人步入四十岁时,他们依然会保持心意已冷的态度喝冰啤酒吗?或者说“白酒秀”代表了一个必经阶段、成熟的前奏和敬业精神?

When these twenty-somes turn forty, will they still uphold the art of chilling out over a couple of cold ones? Or is “the baijiu show” a rite of passage, a harbinger of maturity and professionalism?

我调查了身边的15位中国朋友,结果指向了后者。有位30岁的白酒爱好者说,“一个人越成熟越能干,他就越愿意了解喝白酒的门道。”与此类似,有位28岁的朋友回答说,“年轻人不懂白酒,只有中年人懂得如何欣赏。上个世纪80年代出生的人会为了工作、人脉和朋友而喝酒。90年代出生的人喝酒只是为了看起来很酷。”

A survey of fifteen of my Chinese friends suggests the latter. One 30-year-old baijiu fan commented, “The more mature a person is, the more capable he is of learning how to drink baijiu.” In a similar vein, a 28-year-old responded, “[Young adults] don’t understand baijiu, only middle-aged people know how to appreciate it. People born in the 80s will do it for work, networking, and friends. People born in the 90s do it to look cool.”

除了一位受访者,所有的人都宣称他们“不爱喝白酒”,但是提到了他们愿意喝白酒的几个场合。商务会议、社交活动以及春节合家团聚时,这些都是人们共同的答案,无论男女。这让我意识到白酒不会被更新的酒类所超越,而是白酒将作为权力、传统和友好的象征维持其地位。

All but one respondent claimed that they “did not love” to drink baijiu, but listed a few occasions when they willingly drank it anyway. Business meetings, networking events, and Chinese New Year with the family were common answers for people of both genders. What this suggests to me is not that baijiu is bound to be overtaken by newer products, but that it will maintain its standing as a stronghold of power, tradition, and amiability.

春节的因素也不容忽视。作为中国农历最盛大的节日,春季的到来会让全国在每年2月份左右放假一周。在中国,不断变化的社会现实往往使得人们很少有机会合家团圆。为期一周的春节假期洋溢着热情喜庆,全家几代人欢聚一堂,活动的内容从来都没有变化:大吃大喝。

The New Year factor is not to be overlooked. The biggest holiday on the Chinese calendar, the New Year facilitates a full-country shutdown for a week every February. In China, family unity is often at odds with the reality of its changing society. This week of ultimate reqing brings together several generations of family to unite in a timeless activity: eating and drinking. A lot.

另一位朋友说,“我想,不管我们中国人活到多大年纪,我们都会把白酒作为联系感情的纽带。”

Another friend wrote, “I think no matter how old we Chinese people are, we take baijiu as a connection implement for communication.”

这种态度将在可预见未来保持白酒的地位。在中国,饮酒文化围绕着热情会面打造社会关系,而不是为了喝酒本身。在这层意义上,白酒是交流联络的关键。尽管我所在的公司啤酒销售额飞速增长,表明消费者对高端外国啤酒的意识和兴趣不断提高,但是白酒文化依然有悠久的传统,在其发源地具有坚如磐石的地位。

This attitude is precisely what will keep baijiu in its position for the foreseeable future. In China, drinking culture is centered around forging social connections vis-à-vis reqing rather than drinking for the sake of the drink itself. In this sense, baijiu is the lynchpin of networking. While my own company’s explosive beer sales suggest an increasing awareness of and interest in high-end foreign beers, the baijiu culture is a time-honored tradition with a rock-solid foothold in its homeland.

德里克·桑德豪斯(Derek Sandhaus)是位白酒专家,他将出版一本以白酒为主题的新书,他评论说,“昂贵的白酒把在商界权力和金钱联系起来。只要白酒保持其威望,就能长盛不衰。”

Derek Sandhaus, a baijiu expert with a forthcoming book on the subject, remarks that “Expensive baijiu is connected to power and money in the business world. As long as it maintains its prestige, it’s here to stay.”

那些通过和老板豪饮爬上社会阶梯高出的年轻人可能会把白酒看做职业精神、财富——最重要的是——热情的标志。为此,白酒将继续存在,为热情的酒文化添砖加瓦。只要人们希望与朋友、家人、同事、宾客、生意伙伴、政治家和任何人保持联系,白酒都将洗礼这些关系。

Young people who have climbed the social ladder by drinking heavily with their bosses are likely to consider baijiu a mark of professionalism, fortune, and – importantly – reqing. To this end, baijiu will continue to exist as an essential tile of the reqing mosaic. As long as there exists a desire to bond with friends, family, co-workers, guests, business associates, politicians, and whomever, baijiu will be there to christen the bonds.